IDEAS FOR CHILDREN'S WRITERS

IDEAS FOR CHILDREN'S WRITERSby Pamela Cleaver

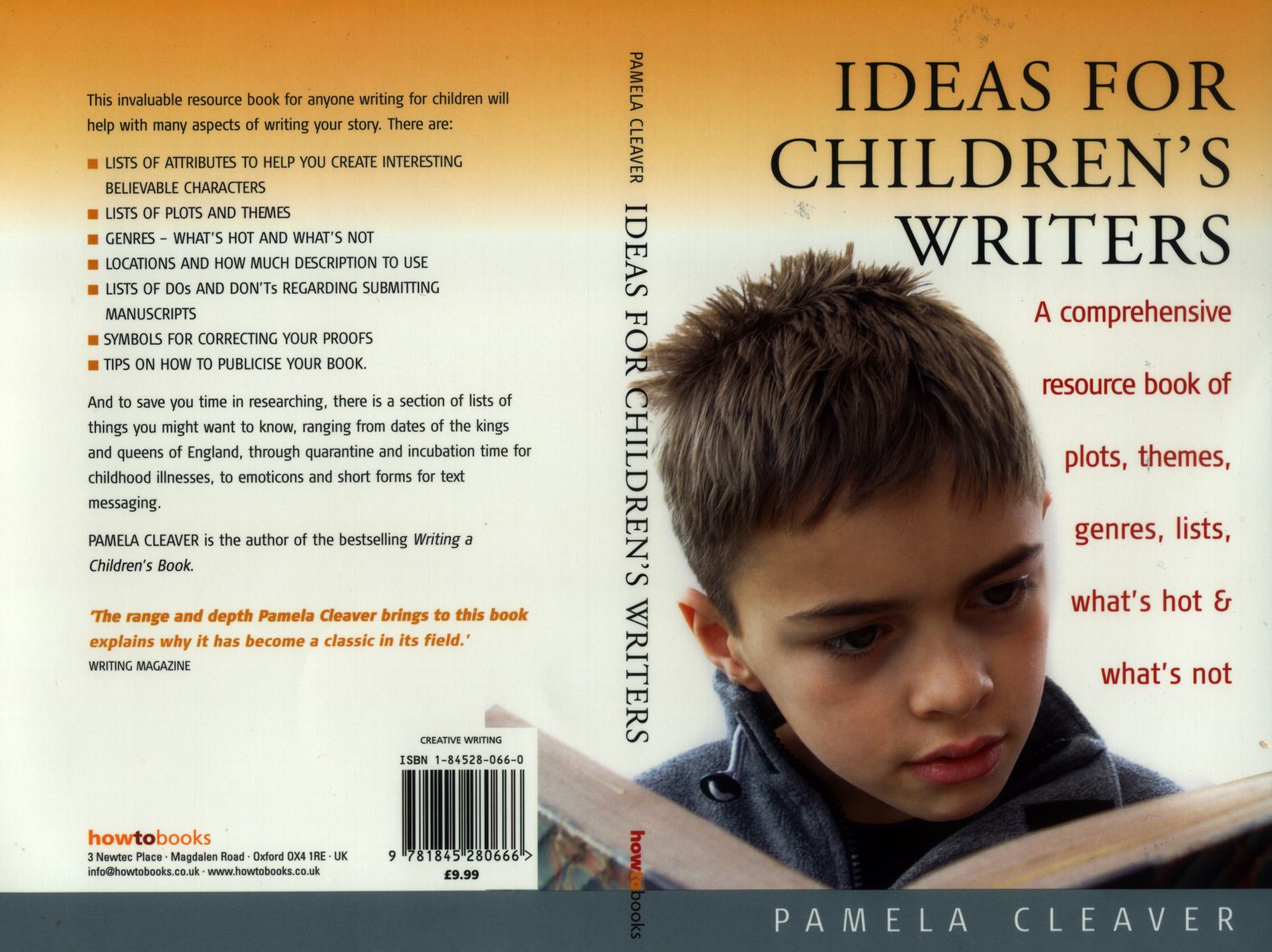

My book IDEAS FOR CHILDREN'S WRITERS is now available (ISBN 1-84528-066-0). This invaluable resource book for anyone writing for children will help with many aspects of writing your story. There are:

- Lists of attributes to help you create interesting believable characters

- Lists of plots and themes

- Genres - what's hot and what's not

- Locations and how much description to use

- Lists of do's and don'ts regarding submitting manuscripts

- Symbols for correcting your proofs

- Tips on how to publicise your book

And to save you time in researching, there is a section of lists of things you might want to know, ranging from dates of the kings and queens of England, through quarantine and incubation time for childhood illnesses, to emoticons and short forms for text messaging.

The first chapter of IDEAS FOR CHILDREN’S WRITERS

The first chapter of IDEAS FOR CHILDREN’S WRITERSLIMBERING UP

Before you tackle writing a story, here are some exercises and ways of thinking about writing for children that you may find helpful. You are going to need a good sized notebook in which to do the exercises, as well as a pocket notebook that goes everywhere with you in which you jot down impressions, thoughts, book titles, newly discovered words, and story ideas. Somerset Maugham said in A Writer’s Notebook, “For my part I think to keep copious notes is an excellent practice ... They cannot fail to be of service if they are used with intelligence and discretion.”

You are your own best resource

For a children’s writer, his best resource is himself when young. OK, so times and customs have changed, but the essential feelings of children have not. Your best resource for child characters is yourself. Find photos of yourself at 5, (starting school) – 11, (moving to senior school) and 13 – (becoming a teenager) and ask yourself some questions.

- What were you like? Did you change a lot between these three landmark ages?

- What did you want at each of these ages? Did you just want to fit in or did you want to be different from your peers?

- If you are one of several brothers and sisters, think about your relationship with the others. Do you fit into the stereotypical pattern in families: eldest child – a leader, the responsible one; second child – competitive, always trying to catch up to older sibling; middle child – the contrary one, always crying, ’It’s not fair!’; the youngest – petted and spoiled, bullied and badgered by turns.

- If you are an only child, did you enjoy being the centre of attention or did you want brothers and sisters, and if so, why?

- What would you have liked to have been like rather than what you were? Would you have liked to have been good at games? Clever? Brave? Popular?

- Would you have liked to have been an orphan (think of Harry Potter, Molly Moon and Tracy Beaker) so you didn’t have parents to interfere? It’s a vexed question in children’s books whether to have parents out of the way, or to have them present. Usually, the younger the character, the more important parents are.

Make some lists:

- List important events in your childhood. They might range from your going to hospital to winning a cup, or failing an important exam. How did you feel about it at the time? What were the consequences? Could you, by altering and embroidering any of these events make a story?

- List places that were important to you as a child – where you went on holiday; Grandma and Grandpa’s house; a castle or museum that you visited and which struck you as amazing, wonderful or interesting. Perhaps there was a den you and your chums built that was the focus of your lives. It may surprise you when thinking of these places how many long forgotten details come to mind. Remember and note down those details, details are what make a place come alive for readers.

- Think of the house you lived in and describe it as you saw it as a child, not the way you would see it now. Remember, things that seem small and commonplace to an adult may seem huge and perhaps intimidating to a child. Were there places that seemed forbidding as well as places that seemed welcoming and cosy? How was it for you?

- Think of the people who loomed large in your childhood apart from parents and grandparents: certain teachers (the nasty ones as well as the nice ones); people in your class; children you played with; neighbours; imposing friends of your parents. Was there someone you hated?Make character sketches of any of these people if you think you could use them (suitably disguised) in your writing.

- What were you scared of as a child? Remembering your fears, both real and irrational, may give you an idea for a children’s story. Writing about it will be cathartic and stories about fears overcome are uplifting and helpful to young readers as well as being popular.

- What were your favourite toys? A beloved bear, a precious doll or a super racing bike could feature in a story. Encourage your imagination to embroider and embellish.

- What did you long for, but never get at the three crucial ages mentioned earlier? You could either make your character get these items, or learn to do without as you did.

- What were your favourite foods? Probably different from today’s children’s favourites, but food is an important ingredient in writing for children. Remember the meal the children had with Mr Tumnus the fawn in CS Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the delicious food in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess brought to her attic by Ram Dass when Sarah was starving.

- Did you have pets? If so, what sort and what was your relationship with them? Books that focus on an animal, telling its life story are hard to sell, but characters who have pets with personality are popular, and the animals can be used to trigger incidents in your plots. Pets can be the focus of humorous incidents that will appeal to children

- What were your favourite books, and why? Could you take the basic idea, or the part that particularly intrigued you, alter the setting, bring it up to date and create a new story. There is a process called bricolage which is taking parts of different stories and using them to make a new one, rather like assembling pieces of fabric to make a patchwork quilt. Remember, there is nothing new under the sun, only new ways of looking at things.

There should be enough material in these lists for you to create a dozen or more stories if you let your mind play with the ideas you have dredged up from your past. Be bold: exaggerate, extrapolate and expand to create something fresh.

Using all your senses

1. Sight

Writers need to be observant. Look out of the nearest window. What do you see? I’m doing that now. It’s a dull day but in front of the window is a crab apple tree full of small red fruits. I see it every day and don’t pay much attention to it, but if I take the advice Miss Tick gives to Tiffany Aching (a trainee witch) in Terry Pratchett’s A Hat Full of Sky, “Open your eyes, then open your eyes,” – what do I see now? I notice the shape of the tree, I see that the little red crab apples look like hanging rubies. A bird alights and begins pecking the apples, shaking the fragile branches. If I were to describe this tree in a story, my second look would give me more material to play with.

Here is a list of some things you might want to describe. Use it to jog your memory, then create your own list.

Sights

- Old houses, castles, churches

- New buildings, townscapes

- Sun shining on a calm sea

- Sea whipped up into angry waves

- Blue skies with white clouds

- Storm clouds

- Colourful sunsets

- Young animals - lambs, kittens, puppies and foals

- Woodland and forests

- Corn rippling in a breeze

- Trees outlined in white frost

- Christmas trees dressed with fairy lights and tinsel

- A crowded market place or mall

2. Sound

You need to open your ears wider than usual too. You need to describe many different sounds when you are writing. Listen to a squeaking door, and try to put into words the sound it makes. Onomatopoeia (words that imitate the sound they describe) is useful here. You hear a dog bark. Does it sound angry or lonely? Music is playing in another room. What kind of music is it? Do you like it or does it get on your nerves? Think of startling noises, and then soothing noises, make notes about them – they will add force to your writing.

Sounds

- Rain beating on windows

- Wind howling round the house

- Music to dance to

- Haunting music that touches you

- Hammer ringing on an anvil

- Hooves of a galloping horse

- An engine revving

- Helicopter overhead

- Church bells

- A fanfare of trumpets

- A siren

- Pneumatic drill

- A scream

- Bells pealing

3. Touch

Try running your hands over different surfaces. There’s the soft velvet of a cushion, the rough surface of a doormat, the smooth feeling of a polished table, the feeling of water running over your hands when you wash, the heat near the stove when a meal is cooking, the cold air when you open a refrigerator door or a freezer. Think of holding a rope or a string that is being pulled tight. Describe it cutting into your hands, and the pain you feel. Tactile writing is vivid and makes the reader feel she is right there with the characters.

Touch

- Brick and concrete

- Silk and velvet

- Sandpaper and bristles

- Slugs, snails and worms

- Rain-soaked clothes after drenching

- Hot sand and stones on a beach

- The softness of animal fur

- Different fruit skins - peach, pineapple kiwi fruit, oranges

- Basket work and sacking

- The chill of ice and snow

4. Scents and smells

Smell is the most evocative of the senses and the hardest to describe. You either have to compare a smell with something else, or mention something everyone knows so your words bring the scent to mind. In A Hat Full of Sky, Terry Pratchett says, “The nose is a very big thinker. It’s good at memory – very good. So good that a smell can take you back in memory so hard it hurts.”

Here is Dodie Smith in I Capture the Castle (Cassandra is in church.) “Then I remembered what the Vicar had said about knowing God with all one’s senses, so I gave my ears a rest and tried my nose. There was a smell of old wood, old carpet hassocks, old hymn books – a composite musty, dusty smell.”

Diana Norman in The Vizard Mask described the smell of a Restoration theatre dressing room, something we do not know but can imagine from the comparisons, “She was enveloped in a smell compounded of orange peel, baize, fish glue, old scent, tobacco and dust.”

Don’t ignore unpleasant smells. The smell of over-cooked cabbage hanging in the air, the nauseating sweetish smell of ether in hospitals, the ammonia stink of fish that has gone off, garlic on someone’s breath, the smell of sweat-impregnated clothes that need washing – all these can be used to point up atmosphere in a scene.

Smells

- Freshly brewed coffee

- Soap

- Smoke from a bonfire

- Fish

- Onions frying

- Exhaust fumes

- Stables and cow sheds

- Old, unwashed clothes

- Sweaty socks and shoes

- Flower scents: rose, lavender, lilies of the valley

- Disinfectant

- Chlorine in swimming pools

- Clean babies and warm puppies

- Meat roasting

- Incense burning

5. Taste

There are four tastes: salty, sour, sweet and bitter. Salt is self-explanatory; lemons and vinegar are sour and make you screw your mouth up. Sugar and all things made with it are sweet, and some medicines like quinine, for instance, are bitter, and so is bad coffee. Food is usually described as ‘delicious’ or ‘disgusting’ at the top and bottom of the approval rating of the taste spectrum, with ’bland’ in the middle. You may need to describe a variety of tastes in your stories.

Don’t forget how closely allied taste and smell are. When you have a head cold, you cannot taste your food. Texture of food is important too. Two members of my family cannot abide anything smooth and slippery such as egg white, and jelly which their siblings love.

One of my favourite descriptions of taste is the liquid Alice drank in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. “Alice ventured to taste it, and, finding it very nice (it had, in fact, a sort of mixed flavour of cherry tart, custard, pineapple, roast turkey, toffee and hot buttered toast), she soon finished it off.”

Tastes and textures in the mouth

- Salted peanuts, Sea water – Salty

- Burnt coffee, Quinine, Aloes, cranberries – Bitter

- Lemon, vinegar, crab apples – Sour

- Chocolate, ice cream, sugar – Sweet

- Toast, crisps, celery – Crunchy

- Egg white, jelly, avocado – Smooth

- Mashed potato, fruit puree – Mushy

- Toffee, tough meat, gum – Chewy

- Chillies, curry, pepper – Hot

Weather

It is important to use all the senses in your writing, it is also essential to let your readers know what time of year it is and what the weather is like. Scents and sounds are affected by the seasons: in spring in the country the smell of fresh grass and spring flowers can be uplifting and the sound of birdsong adds to the atmosphere of well being. But a miserable wet spell, can spoil all this and your character may feel depressed and disgruntled. In summer, suppose your characters have gone to the beach, the salty tang of the sea air, the hot smells brought out by the sun, and the scent of sun-screen everywhere add to the holiday feeling, but if a strong wind blows off the sea and rain pours down and they are cold, they will feel quite differently.

Don’t forget the difference between dark and light, night and day. Imagine going into a house during a power cut. Unseen objects, normally friendly, seem determined to bark your shins or bump your elbow. Think about walking through a wood on a sunny day with the light filtering down through the trees making dappled patterns, then contrast it with walking through the same wood at night when shapes look sinister and the sound of rustling among the leaves presages who knows what?

Make notes on seasonal effects so that when you come to write a winter scene in midsummer, you have references you can use. On a hot, dry day it can be hard to think of grass crisped white by frost, or rainbow colours on the surface of an oily puddle or the fresh smell of a garden after rain. And in winter, will you remember the hot, smells of exhaust fumes in a city street during a heat wave, or the scent of new mown hay in the country unless you noted them down at the time?

Jilly Cooper kept a diary of what she saw on the common near her home while walking her dogs. She noted when certain plants flowered, what birds she saw, how the weather affected the ground underfoot and later she drew on these references when writing her novels. She published these impressions in The Common Years.

Reading

It is vital that writers should read lots of books. It is surprising how many authors say, ‘I am so busy writing that I don’t have time to read.’ They ought to make time. Here are some of the reasons why you should read.

- You need to be constantly aware of what is happening in the market place. You must sample other writers’ books to see what is being published in your field.

- You should check out other authors so that you don’t duplicate plots. Look for ‘holes’ in the market that you could fill. If an historical novelist finds there are dozens of books set in the Tudor period, she may realise it is time to try a different era.

- Read well-known authors to learn from them. How do they achieve their effects? How often do they spring surprises? What kind of language do they use? Do they always end their chapters with a cliff hanger? Learn from the greats how to improve your writing.

- Read to feed your imagination. Read widely outside your field and on subjects you don’t know well. An idea may come from this that will spark a new story.

Conclusion

If you have done some of these exercises you will have plenty of fresh ideas to bring to your writing. You may not want to bother because you are itching to get on with a book or story, but don’t be impatient; there will come a day in your writing when something you noted down is just what you need to help with a description or a character’s reaction.

As Ursula K LeGuin said, “Everything one writes comes from experience. Where else could it come from? But the imagination recombines, remakes ... makes a new world, makes the world new.”

All written material and images related to Pamela Cleaver's work

© 2003-2005 by Pamela Cleaver, unless otherwise noted.

All HTML code and web graphics

© 2003-2005 by Eidolon Studios.